The East-Atlantic Flyway

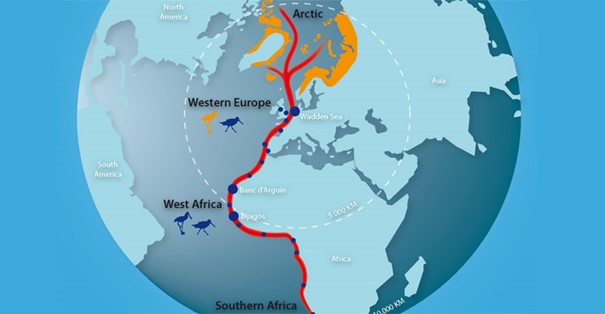

The most important migration routes run along the continental coasts. One of these bird ‘highways’ runs along the west coast of Europe and Africa: the East-Atlantic Flyway. It runs from Eastern Canada and Siberia in the north to the southernmost point of Africa. It is estimated that more than 90 million birds use this route every year.

As you can see on the map, our densely populated delta lies exactly on an important intersection on the East-Atlantic Flyway.

Every year tens of millions of birds of more than three hundred species pass our country on their way.

This strategic position makes the Netherlands a country that is very rich in birds. But it also means that we have a big responsibility to provide a safe haven for all these birds.

Refuelling

Bird species come here to breed, to winter of to take a rest and refuel during their long, tiresome, and dangerous travels form north to south, and back again. They wouldn’t survive if they couldn’t find a large number of spots in our country where they can rest and eat in safety. Without safe resting places, fuelling stations and enough fuel their long trip would be impossible to accomplish. The same goes of course for similar crucial spots in other countries. The whole migration route must offer plenty of safe and nutritious fuelling stations. The quality of the whole route depends on its weakest link; international cooperation is of the utmost importance here.

Dangerous travels

The often-long journeys are not without danger. Threats like predators, harsh weather conditions, hunting and high-voltage cables take their toll every year. But also, the open sea, deserts and high mountains are challenging obstacles the birds must overcome or circumvent. Many bird species avoid large bodies of water and search for the narrowest straits to cross. When you are there at the right moment, in these places bird migration is at its most spectacular. Famous hot spots are for example the Strait of Gibraltar in Southern Spain, the Bosporus in Turkey and, closer to home, Falsterbo in the south of Sweden.

For species that winter in Central and Southern Africa the Sahara can also be a deadly obstacle. Especially when the weather turns bad and sandstorms ravage the region, a lot of birds don’t survive.

Magnificent and mysterious sense of direction

The sublime sense of direction of migratory birds has fascinated us for many decades. Bird ringing research for example proved that a barn swallow that bred in a barn in the Netherlands and wintered in Capetown, South-Africa, in the next breeding season unerring found its way back to the same barn.

We still know far from everything about this phenomenon, but we do know that birds use several senses. This may vary from species to species. Many bird’s species orient themselves with a built-in compass on the positions of the sun, the moon, and the stars. Also, there are strong indications that some birds make a map in their brain, on which they can orient themselves. The coastline and large rivers and water bodies often function as important beacons.

Long distance travellers

Especially insectivorous birds often migrate over huge distances. In summer they find a lot of different insects in Northern Europe, but in winter these are almost absent. Swallows are a good example. In summer they can catch plenty of insects here, but in winter they must depart to more southern places, because of a lack of flying insects. ‘Our’ barn swallows for example winter as far as South-Africa. The same applies to many wading bird species. They are also very fond of insects, supplemented with worms and crustaceans. During the winter months these are very difficult to obtain in Northwest-Europe.

The arctic tern is the long-distance champion. It breeds up to above the polar circle (but also in the Netherlands) and winters around Africa. This bird probably sees more daylight during its life than any other animal.

The other extreme are short distance travellers, like the robin. In winter, this bird species moves for example from Denmark to the Netherlands. The Dutch winters are mild enough for it to survive. The robin you see in your garden in winter is very probably a different robin from the one you saw in summer!

copyright illustrations: Erik van Ommen